by MU Instructional Designers

March 5, 2024

5-7 min read

Effective writing skills are essential, even and because of this new age of generative AI. According to our Writing Across the Curriculum statements:

“To write is to take risks: to reveal commitments and to engage with others. It is an act of permanence, converting listening and speaking into something deliberate, intimate, even dangerous.”

Because writing is so important, we need to think carefully about how we design effective writing assignments.

Make it meaningful.

Writing assignments are a common and essential form of assessment in the classroom, but a key to their success is to make them meaningful beyond the classroom. Similar to our best practices for discussions, you should first examine whether a writing assignment is the best (or even the only) approach to students accomplishing the learning goals. When you assess whether or not a writing assignment is the best route, you’re able to more clearly articulate for students why this assignment is relevant and meaningful. Consider types of writing assignments beyond the traditional academic paper, like web articles, interviews, white papers, etc., which might help students connect their writing to the “real world” (a critical component of andragogy).

Provide opportunities for student voice and choice.

Providing room for student voice and choice in some of the options within an assignment is an excellent way to increase access and inclusion for diverse students (consider Universal Design for Learning [UDL] and Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy [CSP]). As you plan a writing assignment, examine different aspects that could provide students with flexibility in how they complete the task. Could there be options for the topic/focus of their writing or for its style/format (e.g. scholarly essay, popular publication, etc.)? For example, a course goal might be for students to express themselves in an APA academic paper, but they can have a choice in what aspect of the course content they write about. Or, perhaps the goal is for students to analyze a film or composition, and they could choose to do that in a traditional essay format or in the format of a magazine article.

Set clear expectations.

Students need clearly defined expectations in all their assignments. The assignment instructions should articulate the expectations regarding both content and mechanics — how long should the final work be? Is external research expected, and if so with which citation style? Are there style and/or tone expectations (e.g. avoiding the use of first person voice)? Beyond the assignment instructions, samples of student work as well as detailed analytic grading rubrics can greatly clarify expectations (rubrics in Canvas). Check out our Best Practices for Rubrics post for more information on using rubrics.

Provide options for feedback and reflection.

As with any assignment, action-oriented feedback is essential for writing assignments (UDL Consideration 8.5). In particular, feedback opportunities throughout the writing process scaffold student learning effectively. This can take the form of teacher or peer feedback on stages like research question/thesis development, outlines, annotated bibliographies, early drafts, etc. (peer review in Canvas). Once again, rubrics can come in handy here (UDL Consideration 6.4).

In addition to feedback from others, it’s important for students to give themselves feedback on their writing process in the form of reflections and/or self-evaluations. A formalized approach to this could be for writing assignments to be submitted in a portfolio format, with additional documentation and reflection on the revisions made to earlier drafts. Check out “Learning Stories,“ a guest post by Marcus Luther at Jennifer Gonzalez’s Cult of Pedagogy to see an example of how this might work. An approach like this makes it easy for students to easily see the changes in their writing over time. Less formally, surveys or brief written reflections can prompt students to develop those metacognitive skills when it comes to writing (UDL Consideration 9.3).

Scaffold ethical behavior.

When we think about academic integrity and digital citizenship in the context of writing assignments, three concerns come to mind: plagiarism, information literacy/validation, and privacy.

The most effective strategies for promoting academic honesty and avoiding plagiarism are not reactive (e.g. Turnitin) but instead proactive. First, clearly outline your expectations regarding what constitutes plagiarism; international and non-traditional students especially often need this clarification. Second, empower students to be successful without resorting to academic dishonesty. The Writing Center (undergrad) and Heartful Editor (grad) can give students direct feedback and guidance. Self-service tools such as those available on Messiah’s writing program website, the Library research help site, and the Messiah University Writing Center Resources web page can also equip students to research and write effectively. (Check out our annotated bibliography on academic integrity.)

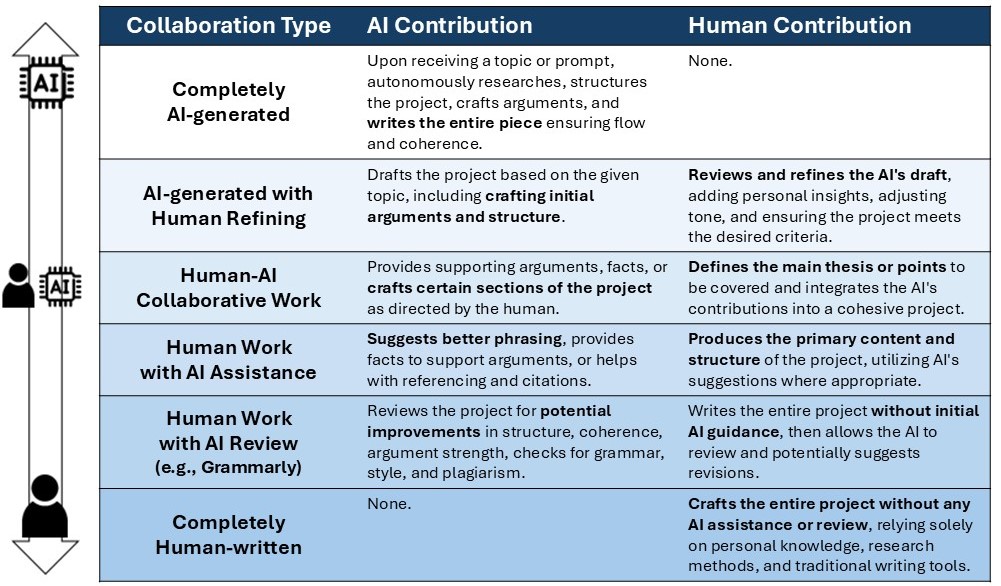

A more recent issue for the integrity of writing submissions is the use of AI tools like ChatGPT. It’s important to be clear about how these tools may or may not be used for any given writing assignment. One helpful framework was shared by Sally Wu of Washington University in St. Louis at the 2023 ITC AI Fall Virtual Summit, which is discussed in “(Re-)Designing Assignments where Students Collaborate with Artificial Intelligence.”

When examining the chart above, determine what level(s) of AI-Human collaboration are appropriate for each assignment, then articulate those expectations for students.

When research is involved in a writing assignment, information literacy/validation is also important. A key component in digital citizenship is the critical thinking skills required for evaluating potential sources for credibility and authenticity. The Library offers extensive support in this area, including asynchronous resources and classroom visits.

Lastly, it’s important to consider privacy in the context of what students write and with whom their work is shared. If student papers will be shared beyond an instructor (e.g. peer review, publication, future samples, Turnitin, etc.), students must be informed early in the process, so that they can choose what to share and not share with others. Encourage students to think critically about the level of personal information they choose to share about themselves.

To learn more about the research on writing assignments, check out our annotated bibliography.