Today’s Photo Friday post focuses not on Ernie Boyer but on his long-time friend and colleague Dr. Ray Hostetter—a man who stood beside Boyer for many years. Hostetter, the sixth president of Messiah College from 1964-1994, passed away on February 12, 2016, at the age of 88.

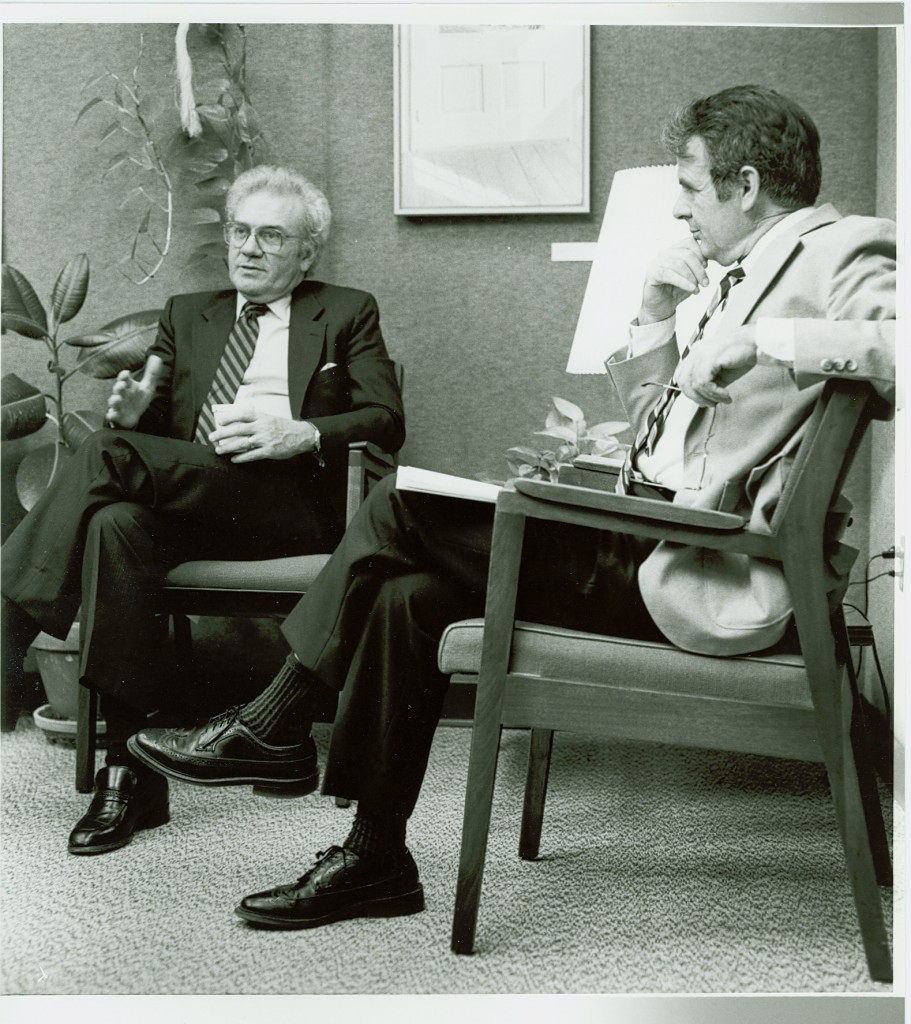

Boyer and Hostetter worked together closely from the 1970s to the 1990s, a period in which Boyer served on the college’s Board of Trustees and Hostetter served as the college’s president. Yet their friendship dates all the way back to 1940s. As students at what was then Messiah Bible College and as roommates at Greenville College, Boyer and Hostetter shared many memories: pulling pranks, playing chess, playing basketball, and attending the same church, among others.

However, the achievements and resulting legacy of Dr. Hostetter is uniquely his own. Throughout his tenure as president of Messiah College, Dr. Hostetter implemented creative ideas to expand Messiah, turning it from “a local school to a college recognized nationwide for excellence in Christian Higher Education.”

One simple way to see this improvement is to look at the operating budget of the college. At the start of Dr. Hostetter’s presidency, the college had a $400,000 budget; by the time he retired the budget had grown to $65 million. This advancement may be attributed to the fact that, prior to his presidency at Messiah, Dr. Hostetter was the college’s vice president of finance and development. Such leadership in finance was essential for raising funds to support the exponential growth in the number of student enrolled.

Another way to understand Dr. Hostetter’s success is to consider the growth of the student body. At the start of his presidency, 250 students were enrolled at Messiah. By the time he retired, 2,300 students were enrolled. As a result of accommodating these new students, the college also expanded its physical plant: it built a learning center, a campus center, a sports center, an arts center, an education hall, and ten residence halls.

Dr. Hostetter also implemented new ideas to expand student opportunities to grow academically and become connected globally. For example, he implemented a cooperative venture with Temple University to create the Messiah Philly Campus. In addition, under Dr. Hostetter, Messiah College teamed up with Daystar University in Kenya to enable Third World students a chance to earn a baccalaureate degree. Both of these ventures helped establish national recognition for Messiah.

However, as board member Harold Engle said, Dr. Hostetter’s dedication to Messiah was most evident in his “dignity, integrity, and humility.” He always acknowledged his accomplishments as a result of “teamwork of board, administration, and faulty, and has given God the glory.”

As a result of what Dr. Hostetter achieved over the course of his life, “anyone who has been near the development of Christian Higher Education would have to say that the accomplishments of Dr. and Mrs. Hostetter were unprecedented.” But it is not just those in academia who see the legacy of Dr. Hostetter. In fact, his legacy lives on in the “thousands of well-trained Christian young men and women who have gone out into the community and throughout the world to witness about Jesus Christ and to share their knowledge and abilities with tens of thousands of others.”

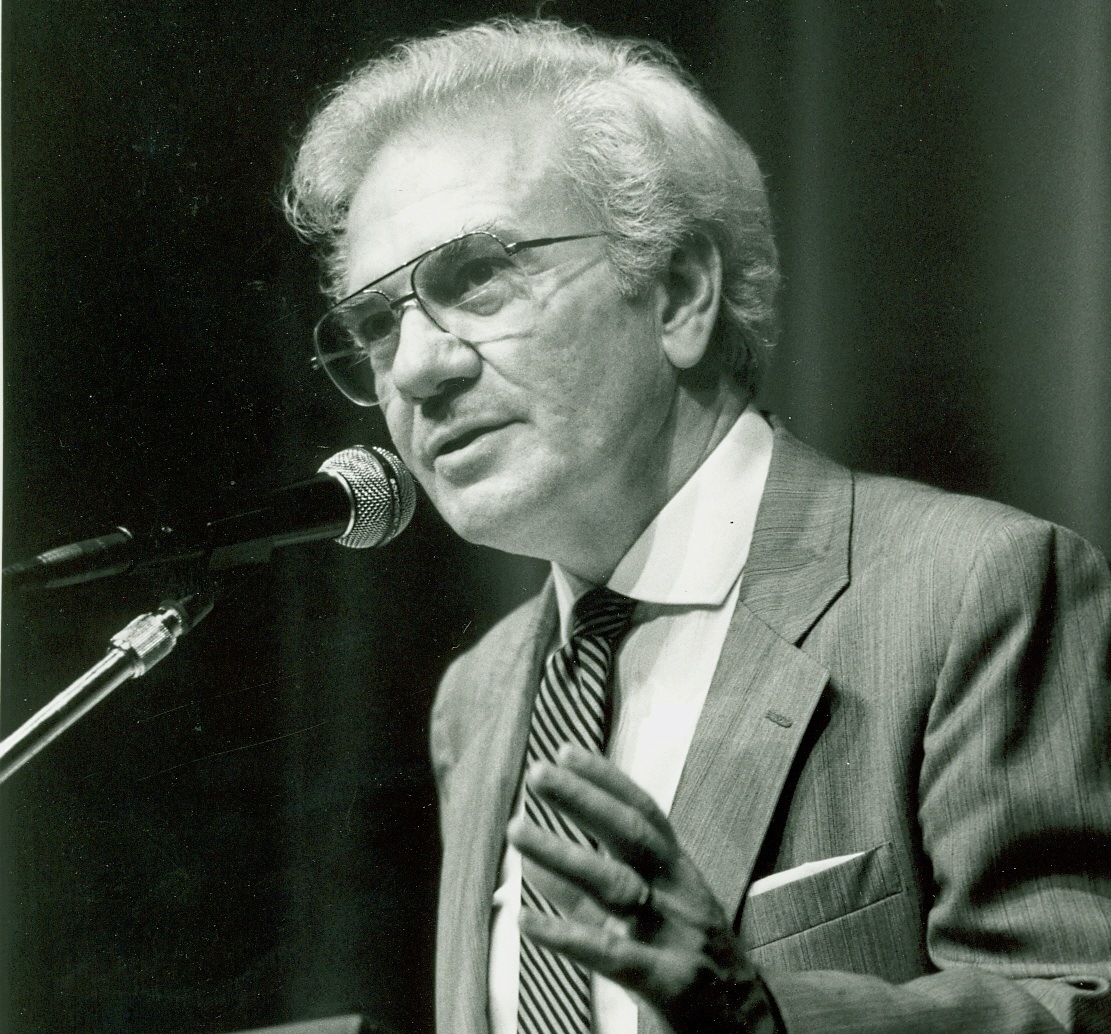

Perhaps Boyer best summarized Hostetter’s legacy when he gave this tribute to his friend during his retirement:

And all of this occurred during Ray Hostetter’s tenure as president of Messiah College. It has been a truly remarkable record of achievement—educationally, spiritually, and fiscally, as well. Under President Hostetter’s leadership an extraordinary institution of Christian Higher Education has been built. And we are all deeply in his debt.