Ernest L. Boyer at a press conference discussing new educational strategies from the federal government. – BCA

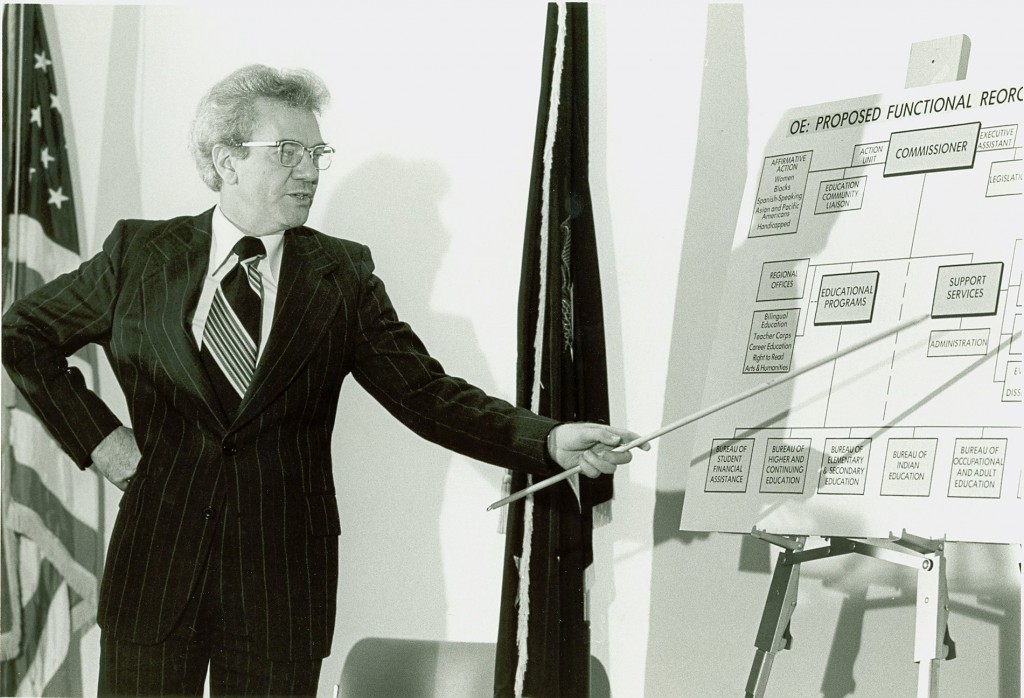

In 1977, Ernie Boyer made the transition from the chancellorship of the State University of New York to the U.S. Office of Education in Washington, D.C., where he served for two years as Commissioner of Education under President Jimmy Carter.

Ever an innovative thinker, Boyer brought a number of changes and new priorities to the “OE,” as the Office of Education was often called by its employees. Today’s Photo Friday highlights some of those changes.

Early in his time at OE, Boyer delivered a talk titled “The United States Office of Education: Reflections and Reaffirmation.” The talk, given during American Education Week in November 1977, traced the growth and development of the OE throughout American history and articulated some key changes for the future.

Here’s a taste of Boyer’s speech:

The United States Office of Education has, [throughout its history], become one of the most diversified, most complicated, and most consequential institutions in this Nation. And every day those of you assembled here come to work at something called “OE,” transforming these empty piles of stone into a living institution. . . .

But here I must strike a more somber note. For it is quite clear to me that the Office of Education — as an institution — also faces problems. Since arriving here I’ve met confusion about the mission of the office. I sensed that many of our colleagues feel trapped in bureaucratic boxes. I’ve also sensed that all too often talents are not fully used. Good ideas go unnoticed, or worse still — they are suppressed. Most seriously, perhaps, we don’t have effective ways to communicate with one another. And we do not develop fully the professional abilities of our staff.

These symptoms are not uncommon to bureaucracies. They are found everywhere. But while OE has its share of problems it has something else as well. We have here a high aspiration for our agency, a reservoir of talent, [and] an eagerness to work for self-improvement, and these are precious assets which also give us special strength.

To read Boyer’s complete address, click here.