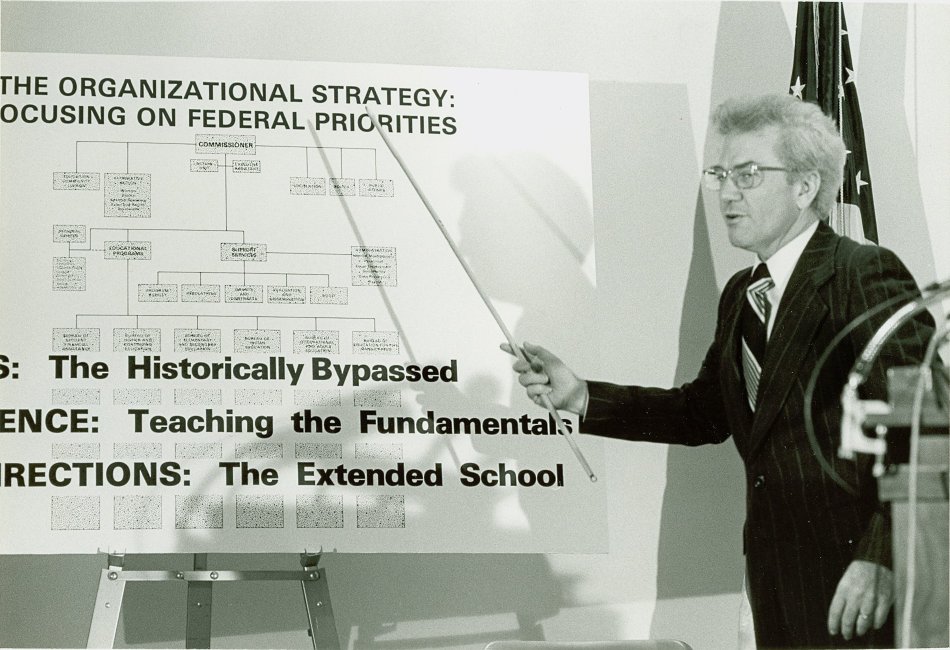

At a 1977 press conference, U.S. Commissioner of Education Ernest L. Boyer discusses new educational strategies for the federal government.

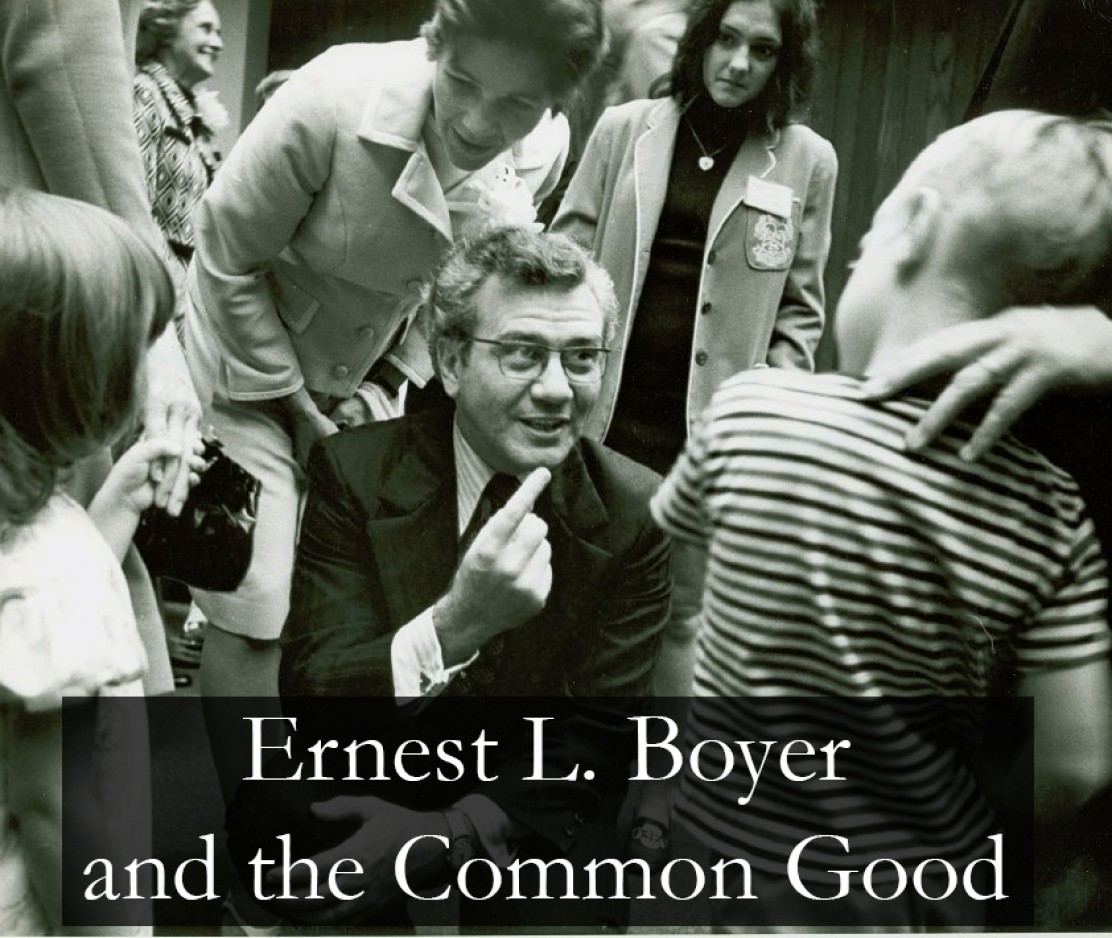

While serving as chancellor of SUNY, in 1976 Boyer received an invitation from President Jimmy Carter to serve as his Commissioner on Education. Boyer accepted, and the family moved from Albany, New York, to northern Virginia. Ernie’s wife, Kay, recalls the challenge that Ernie faced in his new role:

We . . . accepted our move to Washington, D.C., as something providential. We felt we were meant to be in that place at that time and that Ernie was meant to serve as the United States commissioner of education. . . . At age forty-eight, [he] was presiding over an organization with more than 3,000 employees and an annual budget of approximately $9 billion that funded more than 100 education programs. Those efforts ranged from preschool to the postdoctoral level, as well as international programs and student financial aid for proprietary, public, and private school students. As chancellor of the State University of New York, he had led the largest university system in the United States, with sixty-four institutions and more than 350,000 students. I thought that job had been daunting!

I struggled to begin to imagine what life would be like with Ernie filling this new job that seemed impossibly complex. Ernie, on the other hand, was ready to take action and did not feel uncertain.

(To read more of these reflections, check out Kathryn Boyer, Many Mansions: Lessons of Faith, Family, and Public Service [Abilene, Tex.: Abilene Christian University Press, 2014]. This quotation comes from pages 177-178.)

Perhaps part of Boyer’s confidence in his new role stemmed from his deep and abiding educational convictions — convictions that he quickly brought to bear on his work in the U.S. government, both in terms of public policy and in the many speeches and articles he wrote during his tenure.

A page from Ernest L. Boyer’s book chapter titled “Toward a New Interdependence,” published in 1977 while he served as U.S. Commissioner of Education.

Once again, we can see Boyer’s educational commitment to the common good emphasized during his Commissioner of Education years, particularly in a book chapter he wrote in 1977 entitled “Toward a New Interdependence.”

In the article, Boyer cautiously but forthrightly cast a vision for the future of American higher education. The landscape, he wisely noted, was changing — and colleges and universities needed to change along with it, adapting their programs, methods, and even their campuses to meet the needs of late twentieth-century learners. He argued, too, that in an increasingly complex world, students needed an education that pushed them to think not only of themselves but about the good of the societies in which they lived and their undeniable connection to the world as a whole.

First, Boyer contended that colleges and universities needed to update their former ideas about the kind of student to be served. Traditionally, he acknowledged, education was considered to be for the young, who devoted themselves almost exclusively to school from the age of 5 to the age of 18 (and beyond if they pursued a college degree). Classes were scheduled Monday through Friday, from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. Students were expected to pursue their studies full time before they entered the adult world of work. Boyer asserted that this rigid division of life span (student, adult, and retirement) was slowly breaking up. As a result, he further contended, colleges and universities needed to revise their expectations about the average student, creating more flexible programs capable of catering to working students and older adult learners.

Second, Boyer argued that as a result of these demographic shifts, colleges and universities need to revise the techniques they use to deliver an education to their students, rethinking everything from academic calendars to the locations in which classes are taught.

Third, and finally, Boyer urged educators and administrators alike to revise the educational purposes toward which they were directing their students. Rather than articulating the purposes of education in terms of career preparation, he advised them to urge students to understand themselves as inescapably tied to their society and to the world at large. Colleges and universities, Boyer wrote, “must formulate a new, unified central purpose for education.” This purpose, he claimed, should help students “understand more clearly the interdependency of peoples and institutions in our world—not just in an ecological sense, but in a social sense as well.”

Boyer concluded, “We simply must do a better job of alerting our students to the larger contours of their world, of helping them see the broader ramifications of their actions, and of conveying the urgent need to marshal all out resources as we confront the critical choices of the future.”

In this call to educate for a “new interdependence,” we hear once again Boyer’s concern for the common good. Education, he averred, is not a good in and of itself — especially if students use it only to benefit themselves. Instead, he said, education must be for the common good, nurturing a sense of interdependence in students and activating in them a desire to use their knowledge and abilities to create a better world for everyone.

< Re-evaluating the Purposes of the University

NEXT CHAPTER NEXT CHAPTER NEXT CHAPTER >