Messiah alum’s essay ‘Never Lost’ published in travelogue

Elizabeth Arnold ’08 recounts experience of working in Grand Teton National Park in this excerpt of her essay, “Never Lost”

Elizabeth Arnold ’08 recounts experience of working in Grand Teton National Park in this excerpt of her essay, “Never Lost”

In the months between my junior and senior year of college, I took a job wrangling at a guest ranch in Wyoming’s Bridger-Teton National Forest in Grand Teton National Park. I was hoping for nothing more than the chance to ride some good ranch horses and to live — at least for a while — in a place that claims to be “the last of the great West.”

One of my first nights on the ranch, while sitting on the porch of the bunkhouse and looking out into the valley, I watched as the sun disappeared behind the mountains, casting purple shadows across the thick strings of the Buffalo Fork River and the backs of the horses grazing in the lower meadow. I realized in that moment that I would never get tired of the view. No matter how many times I looked out beyond the ranch, the Tetons would always be there, standing behind the river like a promise. And I would always be surprised by how unexpectedly they rose straight and clean out of the valley floor, piercing through thin layers of clouds and cutting into sharp blue sky. In that moment, I knew that this was more than a summer job — that there is a reason people are drawn to this place, to a landscape still wild and powerful.

Just then, Dan, the ranch’s fly-fishing guide, walked over to where I sat on the bunkhouse porch with two coffee cups in his hand. He stood tall and rugged, an embodiment of the Marlboro Man, with a thick, silvered mustache and a worn denim shirt. He handed me a cup and said that the mountains always look better when you’re watching them on a spring night over a cup of black coffee. He leaned against the rail of the porch, set down his cup, and looked out over the darkening space of pasture and willow beds and quick-moving water. He took a long sip and told me that after ten years in Jackson Hole, he’d never gotten tired of the view, because it always had a way of catching him off guard.

I told him I was stunned when I came down Togwotee Pass after my three-day drive to the ranch. I wasn’t embarrassed to tell him that I’d pulled the truck over and stood in the middle of the road awhile, feeling so small, so overwhelmed, looking down at the full spread of the mountains for the first time.

He told me later that evening — when the only sounds on the ranch were the soft and distant bells of horses turned loose — that after coming here for a vacation from a high-pressure job back in Tennessee, this place and the promise of a life spent knee-deep in clear water drew him away from a hundred thousand dollars a year and a pension. “This valley has a way of grabbin’ hold of ya and never lettin’ go,” he said.

I took a long sip. The coffee was almost gone then, and the stars had overtaken the night sky.

In 1825, trapper and explorer Jim Bridger arrived to the Jackson area in search of wealth, Western adventure, and beavers. He spent most of his life learning the intricacies of the region — from the Snake River, Two Ocean Pass, and Gros Ventre Valley to the steep cut of trails carved between the Teton Range and Yellowstone. Bridger knew the paths that would lead him safely over Togwotee Pass or Hoback Junction as he traveled along Jackson’s trapping and trading routes.

But the life of a mountain man is a solitary one, with only a horse, a few mules, and the wide space of a rough and ruthless landscape for company. The promise of seclusion in new and beautiful country — a promise that drew so many westward — was often the very thing some were unprepared for. The isolation, the feeling of being so alone yet surrounded by inexplicable grandeur, was almost too much to handle for many early homesteaders and those who unsuccessfully tried their hands at living off the land and trapping. Some were simply overcome by the loneliness; others fell prey to a land unafraid of showing newcomers they didn’t belong.

This is reprinted from the Spring 2012 issue of The Bridge magazine.

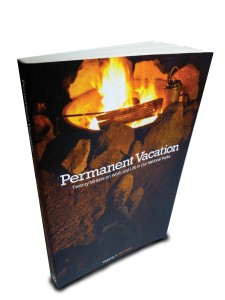

The essay, “Never Lost,” written by Elizabeth Arnold `08, was recently published in the book, “Permanent Vacation: Twenty Writers on Work and Life in Our National Parks, Volume I: The West.”