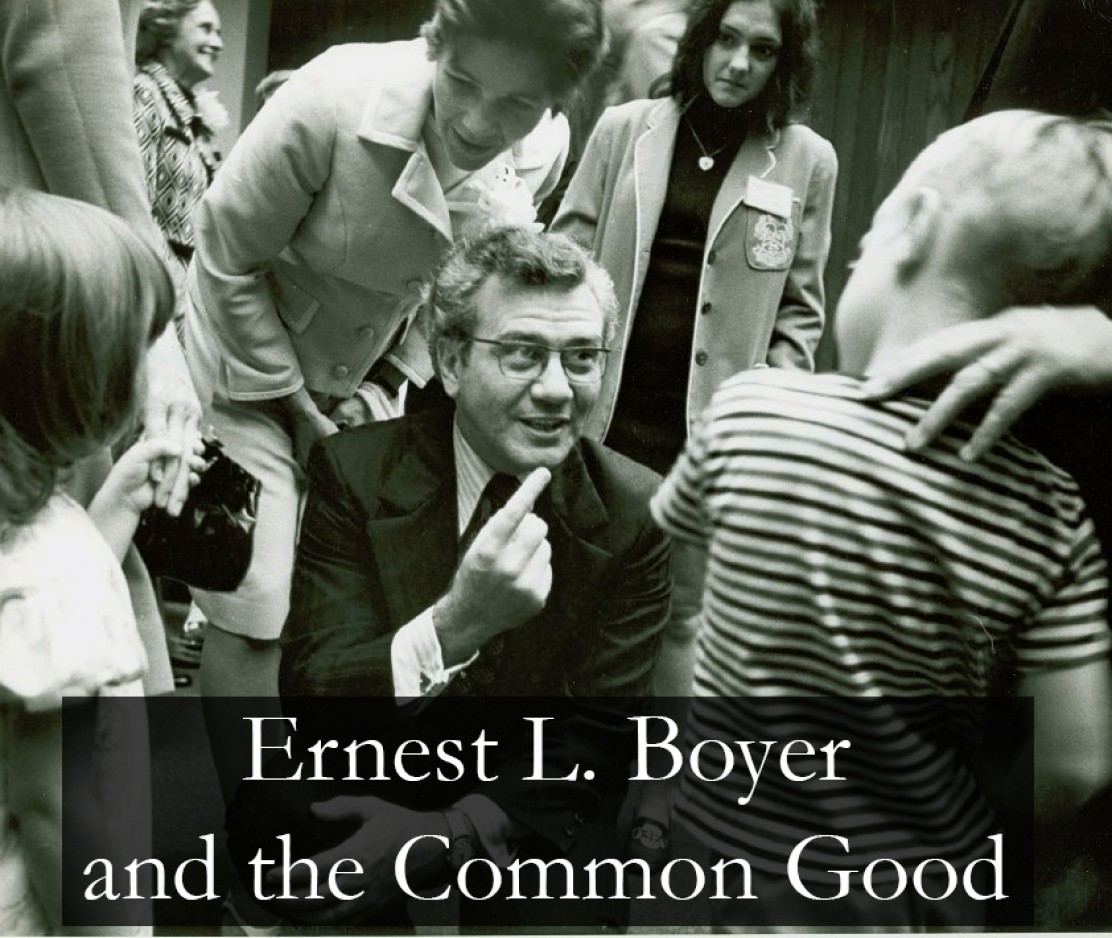

Ernie Boyer and his mother, Ethel, outside their home in Dayton, Ohio, in 1945, shortly before Ernie left to serve alongside other young men from the Brethren in Christ Church as a “seagoing cowboy.”

The religious community in which Ernie Boyer was born and raised, the Brethren in Christ, were pacifists. During times of war, they refused to enlist in the military. Yet they coupled this war resistance with active service toward those devastated by conflict. During World War II, the Brethren in Christ carried out this commitment to service alongside other religious pacifists, including Mennonites and Quakers, and participated in various programs designed to aid those people hit hardest by the war.

One program, affectionately referred to as the “seagoing cowboys,” was organized in cooperation with the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration. The program had a very simple premise: shipping much-needed livestock from the United States to other countries. In the years following World War II, more than 7,000 men and women—the aforementioned “cowboys”—accompanied shipments of cattle, pigs, goats and other livestock across land, sea, and air to deliver them to families in Europe. (This program eventually led to the establishment of Heifer International, which continues to this day as a humanitarian organization supplying livestock to individuals and communities in need.)

In 1946, at the tender age of 18, Ernie Boyer became one of the seagoing cowboys. He was at the time freshly graduated from Messiah Academy, the high school program of what was then called Messiah Bible School (now Messiah College). And he, along with several of his classmates, responded to the call of the Brethren in Christ Church for able-bodied men committed to sacrificial service who were willing to donate several weeks of their lives to alleviate the suffering of war survivors in Europe.

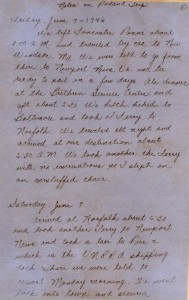

One of Ernie Boyer’s first entries in his diary while serving as a seagoing cowboy delivering U.S. livestock to war-torn Poland in 1946.

During his seagoing cowboy journey, Boyer often jotted down short diary entries documenting the day-to-day experience on the sea and in Europe. He also took numerous photos, both on the ship and on land. Taken together, these entries and photos offer a glimpse into one of Boyer’s earliest experiences of direct human service.

Boyer’s diary entries and photos were later compiled, probably by Boyer’s wife, Kay, into a scrapbook. The scrapbook is now available in the Boyer Center Archives.

The ship on which Boyer and his classmates traveled, the Wesley Barrett, set sail from Newport News, Virginia, en route to Danzig, Poland, on June 12, 1946. It would seem from the earliest diary entries that Boyer didn’t get his sea legs too quickly. Here’s a snippet of the entry from his first day at sea:

Got up at six which was our regular rising hour. I began to feel dizzy and so did most of the fellows. I didn’t do much work. Sent my breakfast and dinner overboard. I was alright laying down but when I tried to walk I would get dizzy again. I was lucky though. By the afternoon I was feeling O.K.

On the sea, Boyer and his shipmates encountered a few unexpected complications, including this one, on June 22:

Had a rather interesting experience today. About two-thirty I felt our engines stop so went topside to see what the trouble was. I discovered we had been hailed by the Boulder Victory and were given [a] stowaway from that ship to take back to Poland.

Meeting this refugee clearly affected Boyer, and he hinted at this fact in a rather short addendum to the same entry:

He was a young fellow who was going to try to get to his uncle in New York City. His parents were dead. I gave him a shirt and he seemed thankful.

This face-to-face encounter with the ravages of war foreshadowed the destruction and devastation Boyer would witness firsthand when the Wesley Barrett docked in Danzig on June 27. The next day, Boyer’s first day on land, he wrote:

The destruction is almost beyond description. Block after block of houses and buildings completely destroyed and laid to the ground. Children would flock around us and beg for cigarettes and candy. It is surprising how soon you become accustomed to the destruction and poverty and hardly notice it. That is the shame of it.

Ernie (back row, sixth from left) and his fellow “seagoing cowboys” aboard the Wesley Barrett en route to Europe.

After delivering their payload of livestock, Boyer and his shipmates set sail for America on July 2. The trip took 16 days and in the end the boat docked in Montreal, Quebec (a development that Boyer does not explain in his diary). And in his last entry, on July 18, his plans for getting back to his home in Dayton, Ohio, are only tentative, to say the least: “I am thinking now of hitch-hiking home. Anyway, it will be good to be back in the states.”

Boyer doesn’t close his trip diary with any extended meditations. He does not reflect on his own religious faith or the way that it’s been transformed. Nor does he write about the importance of other-oriented service or the civic necessity of putting a neighbor’s needs before one’s own—the kinds of themes he would explore extensively in his later writings. But it is interesting to imagine Boyer, many years later, sitting down to write his book High School: A Report on Secondary Education in America. In it, he proposes a new emphasis on service in the high school curriculum, a program that would

help students see that they are not only autonomous individuals but also members of a larger community to which they are accountable. . . . It would help break the isolation of the adolescent, bringing young people into contact with the elderly, the sick, the poor, and the homeless, as well as acquaint them with neighborhood and governmental issues (209-210).

A notecard from the Brethren Service Committee thanking Ernie for volunteering with the livestock project.

Clearly, Boyer does not explicitly draw on his own high school-age service experience in crafting this new vision. But, of course, he knew those benefits firsthand.

It’s probably not wrong to imagine that many of the seagoing cowboys signed up for the task because they sought a sense of adventure. The journey gave them a chance to see the world, meet new people, and collect new experiences. Boyer himself was probably thrilled to have this experience. But it’s also possible to imagine that, despite his youthful excitement, Boyer was deeply affected by the the joy of serving others in need and by making a small but powerful impact on a single community. Inspired by his family’s generational commitment to service and by his growing-up years in a peace church, Boyer’s journey to post-war Europe undoubtedly shaped his future career and his educational vision of the common good.