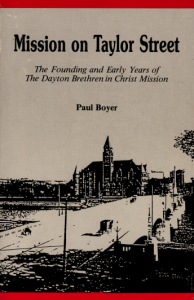

In this 1987 book published by the Brethren in Christ Historical Society, the distinguished American historian Paul Boyer (brother to Ernie) wrote about his grandfather, William Boyer, and his work as the founding minister of the Dayton Brethren in Christ Mission, a church that served poor, working-class communities in inner-city Dayton in the early twentieth century.

Ernest L. Boyer was born into a family committed to service.

His grandfather, William Boyer, was a minister in Brethren in Christ Church, a small religious community similar to Mennonites, and for most of his life he combined his call to preach with his desire to minister to the neediest in society. In 1912, Boyer was assigned by the church to move into inner-city Dayton, Ohio, and start a mission church. At the time, Dayton was a major industrial hub in the United States, afflicted with all the social ills that plagued urban communities in the early twentieth century: poverty, disease, substandard housing, lack of basic city services such as waste management. The city’s hundreds of thousands of industrial laborers worked long hours in dark and dangerous conditions. It was into these difficult conditions that William Boyer moved himself and his family when he founded the mission on Taylor Street. He and his wife would remain there for the next four decades.

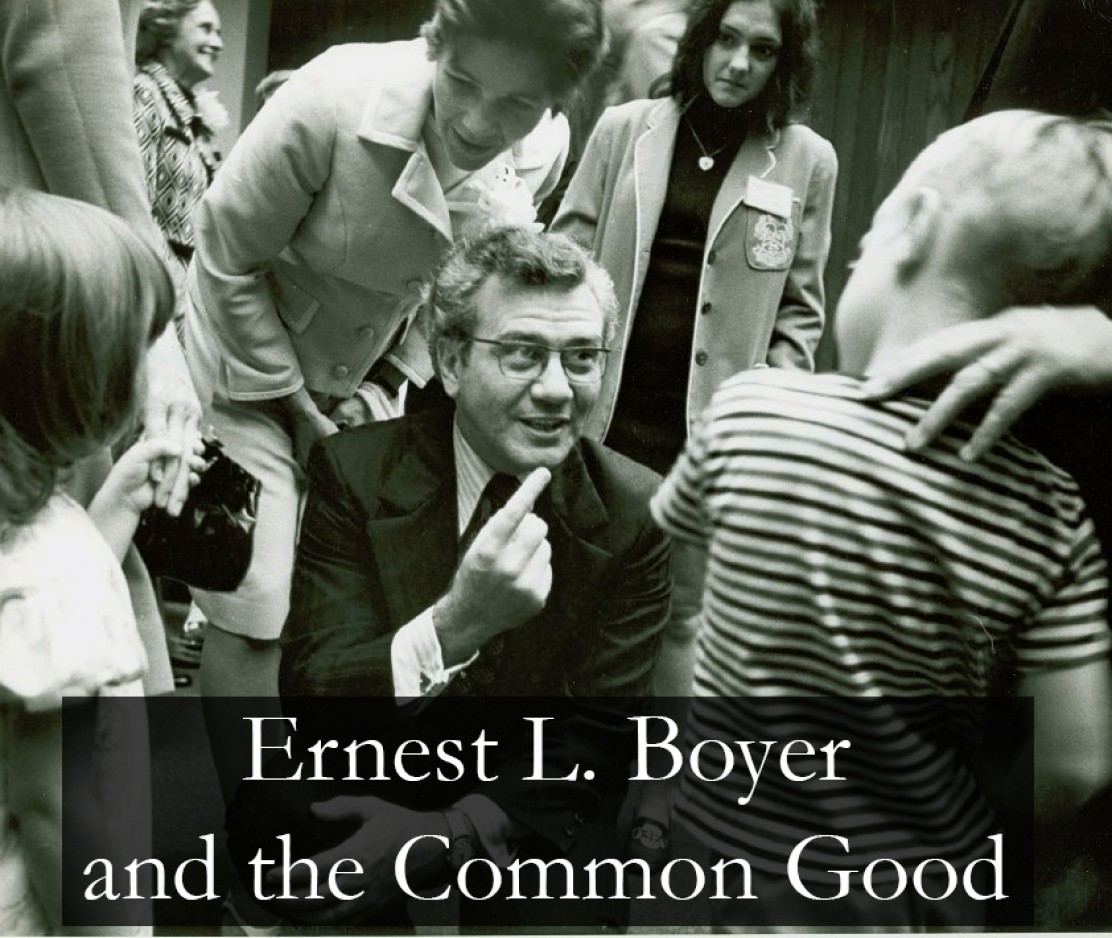

Ernie Boyer often spoke admiringly of his grandfather and his work in inner-city Dayton, as in his 1995 speech entitled “The Basic School“:

At the age of forty, Grandpa Boyer moved his little family from a pleasant residential neighborhood in Dayton, Ohio, into the slum area, as it was called in those days. He lived in that community for forty years, running a city mission to help the poor. . . . As I watched my grandfather work with people who were impoverished, I began to understand that to be truly human, one must serve.

By his own admission, Boyer absorbed a commitment to service from his grandfather. But, to be clear, William Boyer had one kind of service in mind: the salvation of souls. As a Christian minister, he desired to convert people to Christianity and believed, for better or worse, that any social ills they experienced — poverty, illness, family dysfunction, child neglect, and more — could be solved by turning to religious faith. According to Paul Boyer, Ernie’s brother and a distinguished American historian, who wrote about his grandfather’s ministry in the 1987 book Mission on Taylor Street, William Boyer “was concerned first of all [with] the spiritual needs of the people” (79) — hardly an endorsement of the common good.

And yet William Boyer, unlike some city missionaries of his day, never looked down upon the people he served. He recognized their intrinsic worth and value as human beings, and cared for them — whether spiritually or physically — in ways that validated their humanity. As Paul Boyer wrote, “William Boyer’s belief in the dignity and human worth of each individual, whatever his or her obscurity, shortcomings, or failures, underlay his approach to . . . all aspects of his ministry” (120). Perhaps this commitment to the worth of all people would inspire an adult Ernie to embrace a more capacious notion of the common good and combine it with his grandfather’s commitment to service.

The Boyer family’s generational commitment to service shaped young Ernie’s life in many ways, but perhaps none more obvious than his teenage decision to aid war-torn Europe in the wake of World War II.