Today we visited sites of civil rights protests in Alabama, mostly in Montgomery and Selma.

The first was the Lowndes County Interpretive Center, in White Hall, AL. In 1964, this county was the site of intense racism, inequality, deprivation, intimidation, and violence. While 80% of the county was made up of African Americans, it did not have a single African American registered voter! The interpretive center is administered by the National Park Service.

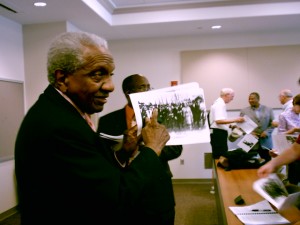

Immediately thereafter we went to Wallace Community College to meet with Rev. Frederick Reese who was President of the Dallas County Voters League (DCVL) who spoke to us about his experiences organizing voting marches and protests and trying to increase the number of voters in the county (the real increase in numbers came later with the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964). Sprightly, articulate and looking a youthful 82 years, he gave an account of the teachers march in Selma, Alabama in 1965. Central to his protest and demand for equality was his Christian faith and he made no excuses for it. He remains convinced that it was his faith that sustained, motivated, and empowered him to act as he did. He figures prominently in surviving videos of the civil rights movement in Selma. We also met James Perkins the first African-American mayor of Selma (2000-2008).

Lunch was at a soulfood buffet on Highway 80 called “Plantation Inn” and provided a rich fare of corn, okra, collared greens, fried & grilled chicken, pork, black beans, broccoli, mashed potatoes, macaroni & cheese topped off with peach cobbler, bread… The story of how this repertoire of culinary meanings and practices that make up soulfood was assembled is a fascinating one, but its retelling will have to await another occasion. But you might recall Jake Diaz’s presentation on this subject at Messiah in February 2011.

At “Plantation” we were introduced to Ms. Joanne Bland, a civil right activist who was 11 years old when she participated in the “Bloody Sunday” march from Salem to Montgomery (7 March 1965). In particular she experienced the brutality of state troopers who rushed the marchers at the, now infamous, Edmund Petters bridge assault. She spoke about her experiences with a caustic wit that was irreverent to the niceties of polite conversation. Her accounts of life in pre-integration Salem revealed the deep unrelenting, daily brutality of segregation in the south. From riding buses, to treatment in offices, the patronizing gaze of the wealthy elites of plantation society, and the terror tactics of the KKK clearly brought the situation to a boil by the early 1960s.

Ms Bland took us through a tour of Selma and we saw the different sections of the city which was by and large integrated (barring the golf course!!). We visited the Zion United Methodist Church (where the protesters commenced their marches), the Perry County jail, the Jimmie Lee Jackson Gravesite (killed during the protests while trying to shield his mother from a state trooper), and the National Voting Rights Museum and Institute (which was under renovation). We also visited the Edmund Petters bridge, mentioned earlier, and it was touching to be at the same spot that had seared the conscience of a nation and the world in 1965.

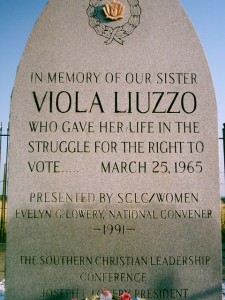

On the way back to Montgomery we stopped to visit the Viola Liuzzo Memorial (see previous post). This was followed by dinner was at a diner called Dreamz, whose owners were involved in civil rights cases calling for integration of the schools in Montgomery.

Visiting smaller places like Selma gave me a valuable insight into the personal perspectives of participants in the Selma to Montgomery march. In a city of Atlanta, discerning the racial divide required some digging around, whereas in Selma, it seemed to be lying just below the surface. I also realized that the Civil Rights movement has no single narrative. Rather, it is made up multiple narratives that sometime jostle to find expression in the public sphere. Since some of these sites are of national historic value, they fall under the jurisdiction of the state and its agencies which invariably try to insert “an official” voice into the brochures, notice boards, and audio visual presentations. Nowhere did this become so clear as in front of the Zion United Methodist Church in Marion, Alabama. Here a National Park Service information board on the Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail announced that a the “American people” were the “confluence” of “two fundamental ideals”—“democratic equality and nonviolent protest”! Certain white groups would no doubt have another view of these events and their memorials. For instance, one notice posted by a southern group in Selma’s Town Hall declared a sesquential celebration of the “War for Southern Independence” a.k.a the Civil War. In addition to this the surviving participants of the civil rights movement have their own memories, understandings, rememberings and forgettings that do not always coalesce to create a neat linear narrative. The Civil Rights movement is a diagnostic event that captures the agency of a variety of historical actors—the agency of ordinary people, memory, state and nationalist erasures or incorporations of local events and histories to produce the national character of a people…the list could go on and on…And then there are the painful stories of segregation, too painful to share here…

The racial divides persist here in Alabama and elsewhere…