iPad experiment

You might not expect a historian of Medieval and Renaissance Europe to be among the first educators at Messiah College to volunteer to lead a pilot project exploring the impact of mobile technology—in this case, the iPad—on students’ ability to learn. But that’s exactly what happened.

You might not expect a historian of Medieval and Renaissance Europe to be among the first educators at Messiah College to volunteer to lead a pilot project exploring the impact of mobile technology—in this case, the iPad—on students’ ability to learn. But that’s exactly what happened.

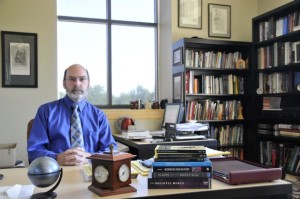

Joseph Huffman, distinguished professor of European history, and the eight students in his fall 2011 Intermediate Latin course exchanged their paper textbooks for iPads loaded with the required texts, relevant apps, supplementary PDFs and a Latin-English dictionary. The primary goal was to advance the learning of Latin. The secondary goal was to determine whether the use of the iPad improved, inhibited or did not affect their ability to learn a foreign language.

Why Latin?

“A Latin course is about as traditional a humanities course as one can find,” Huffman says. Because any foreign language course requires deep and close readings of the texts, studying how student learning and engagement are affected by mobile technology is especially provocative in such a classic course. In addition, Latin fulfills general language course requirements and, therefore, classes are comprised of students from a variety of majors with, perhaps, diverse experiences with mobile technologies like iPads.

One aspect of the experiment was to explore whether students would engage the learning process differently with an iPad than a textbook. The assumption, Huffman admits, is that today’s students likely prefer technology over books.

Huffman’s experiences with his Latin 201 course—comprised of five seniors, two sophomores and one junior—challenged that commonly held assumption.

Outcomes

A survey administered to students at the conclusion of the Intermediate Latin iPad experiment revealed some surprising advantages and disadvantages to the iPads.

Some of the benefits that students noted were having their textbook, dictionary and PDF texts all in one place and utilizing a helpful app to make interlinear notations directly within PDFs. “It was convenient to have all the books and materials on one device in terms of carrying them all around,” affirmed one student.

“We can conclude with clarity and certainty,” Huffman states, “that the introduction of portable digital technology is not a challenge to the learning process but rather has inherent benefits.” Students’ learning experiences, he goes on, can be enhanced through the use of the technical literacy they employ in their everyday lives.

Students were less enamored with some of the limitations of their electronic textbook which required its own commercially-produced app (Kobo) that was not able to make interlinear notations. In addition, there were inevitable issues with network connectivity that disrupted class or a student’s personal study time. Additionally, students noted that the experience of reading in a scrolling fashion rather than a more traditional, less linear style of reading was very challenging. (Think, for example, of how helpful it is to be able to recall a passage’s physical location within a book compared to reading in an up-down fashion, screen after screen on devices like the iPad.) One student noted, “[It was] extremely difficult to orient myself—I could not see where I was in the book.”

Perhaps one of the most interesting comments about the experiment came from the student who observed, “I felt a severe lack of connection to the Roman/Medieval culture using the iPad. Although it’s rather silly, one of my favorite things about Latin is the fact that we’re reading texts as they were originally intended. I’m not sure why, but I felt something was lost in the tradition of Latin.”

A fascinating experiment

All in all, Huffman says, the project was a fascinating experiment with rather neutral results as to whether mobile technology improves a student’s learning. “There is nothing inherently ‘richer’ in digital book formats than currently exists in traditional printed book formats when it comes to student learning in the humanities,” Huffman wrote in his concluding report. “Students made it very clear that, irrespective of the format used to deliver them—whether printed or digital—the locus of student learning was always the texts themselves.”

Messiah continues to experiment with the use of iPads in a variety of disciplines. During this spring semester, for example, nursing and visual art students are testing the technology in their respective fields alongside poets and student teachers in what is indeed a “fascinating experiment” about the impact of mobile technology on student learning.

April 16th, 2012 at 3:22 pm

[…] the rest here. Share this:FacebookLike this:LikeBe the first to like this […]

April 16th, 2012 at 3:43 pm

[…] Messiah College: Messiah News – Messiah College Homepage Features » iPad experiment. Share this:FacebookEmailStumbleUponTwitterLinkedInLike this:LikeBe the first to like this […]

May 31st, 2012 at 7:53 am

[…] This year several faculty of the Department of History at Messiah College were awarded Innovative Technology and Learning Grants from the Information Technology Services department to experiment with the use of iPads for the purpose of student learning and faculty-student research. My colleague Dr. Jim LaGrand used iPads in his public history class (HIST 393) to communicate findings in public history. Another history colleague, Dr. Joseph Huffman, used iPads in Latin 201 to read e-texts, with the goal of determining how the devices influenced learning a foreign language (you can read about the results of his experiment here). […]